Computational knowledge: Wikidata, Wikidata query Service, and women who are mayors!

By Trey Jones, Senior Software Engineer, Search Platform, The Wikimedia Foundation

A question that has been near and dear to the hearts of fans of Wikidata and the Wikidata Query Service (WDQS) for many years is: What are the world’s largest cities with a woman as mayor? (No really! The Wikiquote page for Wikidata includes a quote from and a link to a 2015 mailing list message from Markus Krötzsch saying he’d been using it as an example for years. It was mentioned in a TechCrunch article all the way back in 2012 and has come up more recently in an October 2019 interview in Newfoundland Quarterly, and a February 2020 article in Wired.)

It seems like a straightforward question, and, if you think about it, all of the information needed to answer it should be right there in English Wikipedia. The largest cities in the world should have articles that list their mayors, and there’s already a list of the largest cities in the world. For each city, we can just open the city’s article, see who the current mayor is, and note whether or not the mayor is a woman.

Great! Let’s say we only want the ten largest cities with women mayors. After going through the eleven largest cities on the list, we find the largest city with a woman as mayor is Tokyo (Governor Yuriko Koike)—oh, yeah, we would have to figure out that the equivalent of “mayor” in Tokyo uses the title “governor,” and if we aren’t conversant with Japanese names, we’ll have to look up that “Yuriko” is a woman’s name. Okay, that’s one!

The next two largest cities with women as mayor are Mumbai (Mayor Kishori Pednekar) and Mexico City (Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum). They are 14th and 32nd on the list. This is clearly going to take a while!

Unfortunately, there’s another wrinkle: the English Wikipedia list of largest cities only lists 79, and we are going to need more than that to find ten with mayors who are women.

Enter Wikidata

You have probably guessed that there is a much better method to get to the information on women mayors faster and more easily using Wikidata and WDQS.

One of the main aims of Wikidata is to represent knowledge in a way that is computable—that is, amenable to automatic processing. Wikipedia already contains a lot of information; much of it is reasonably easy for a human to understand—though some of the more esoteric bits are decidedly not—but it’s not at all readily crunchable by a computer.

Another project, DBpedia, has a similar aim by way of a more ambitious method—automatically extracting information directly from Wikipedia. But natural human languages are hard, and extracting information from text will always be, at least to some degree, language-dependent. Even infoboxes, which on-wiki are used to present a human-readable summary of key information, can be too noisy for perfectly accurate automated processing—because humans always allow for exceptions, extensions, and unexpected variations—and the details of infoboxes vary across wikis. With lots of clever heuristics and post-extraction cleanup, you can get pretty far with automated extraction, but it requires a lot of sophistication and a fair amount of manual effort.

The Wikidata approach is a time-tested one: offload all the really hard language and knowledge processing to a human, and let people encode the knowledge directly.

Triple the pleasure, triple the fun!

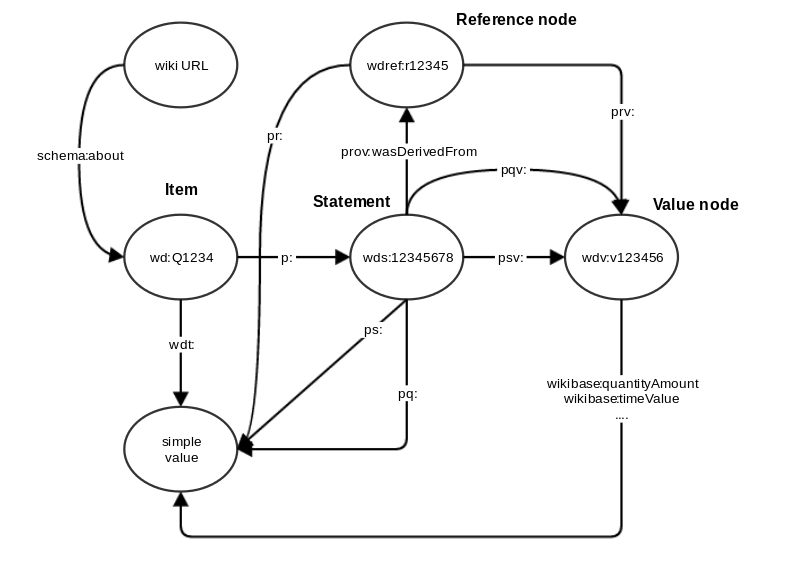

There’s a lot of information out there to encode, but if we want computers to be able to process the information once we encode it, it’s best to keep the representation simple and consistent. Fortunately, this is a fairly well-solved problem—semantic triples represent information as simple “subject, predicate, object” relationships.

To represent a bit of knowledge like “Yuriko Koike is a woman and the mayor of Tokyo (pop. 13,929,286),” we’d break down the relationships among the entities into semantic triples: “Yuriko-Koike has-gender female,” “Tokyo has-population 13,929,286,” and “Tokyo has-as-head-of-government Yuriko-Koike.” Of course, these still don’t capture the whole story, and they assume some additional background information, like “Yuriko-Koike is-a person” and “Tokyo is-a city” and so on. Computers are often very fast, but generally very dumb, so in a system of explicit representation of information, you have to tell them everything. Tokyo is a city. The sky is up. Water is wet. Mayors are people. (Unless they aren’t!)

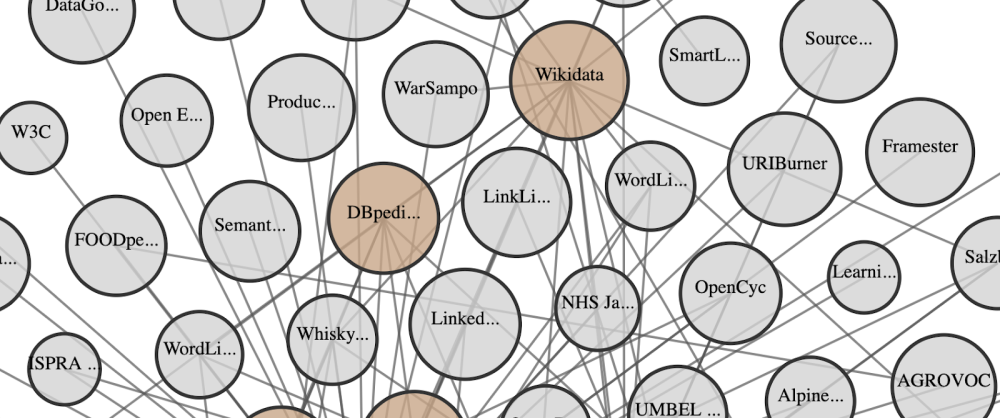

Semantic triples are used as part of a group of specifications called the Resource Description Framework—a name, by the way, that everyone forgets in favor of its acronym: RDF. The full details of RDF are complicated, but it reflects several of the important principles on which Wikidata is built: data should be encoded in a way that is neutral with respect to computing platform (operating system, programming language, low-level data representations, etc.) and compatible with other efforts in knowledge representation (like Linked Open Data, which includes a huge number of open data sources).

Wikidata takes the platform neutrality a step farther and also upholds the principle—at least in theory—of language neutrality as well. In practice, there’s a lot more information in Wikidata in English than there is in Nyanja, but the core representation is language agnostic. Yuriko Koike isn’t identified primarily in Wikidata as “Yuriko Koike” or “小池百合子”—instead, her designation is item Q261703. Similarly, the relationship we talked about as “has-gender” above is actually property P21. If you are new to Wikidata and you follow those links, you’ll probably see most information in English, but if you log in and change your preferred language, not only will the interface language change, so will the descriptions and labels of items and properties, when they are available in your language of choice.

Along comes Wikidata Query Service

With more than 79 million items, 1.1 billion edits, and almost a billion statements—and those numbers are surely out of date already! —Wikidata certainly contains a lot of information—but what can we do with it?

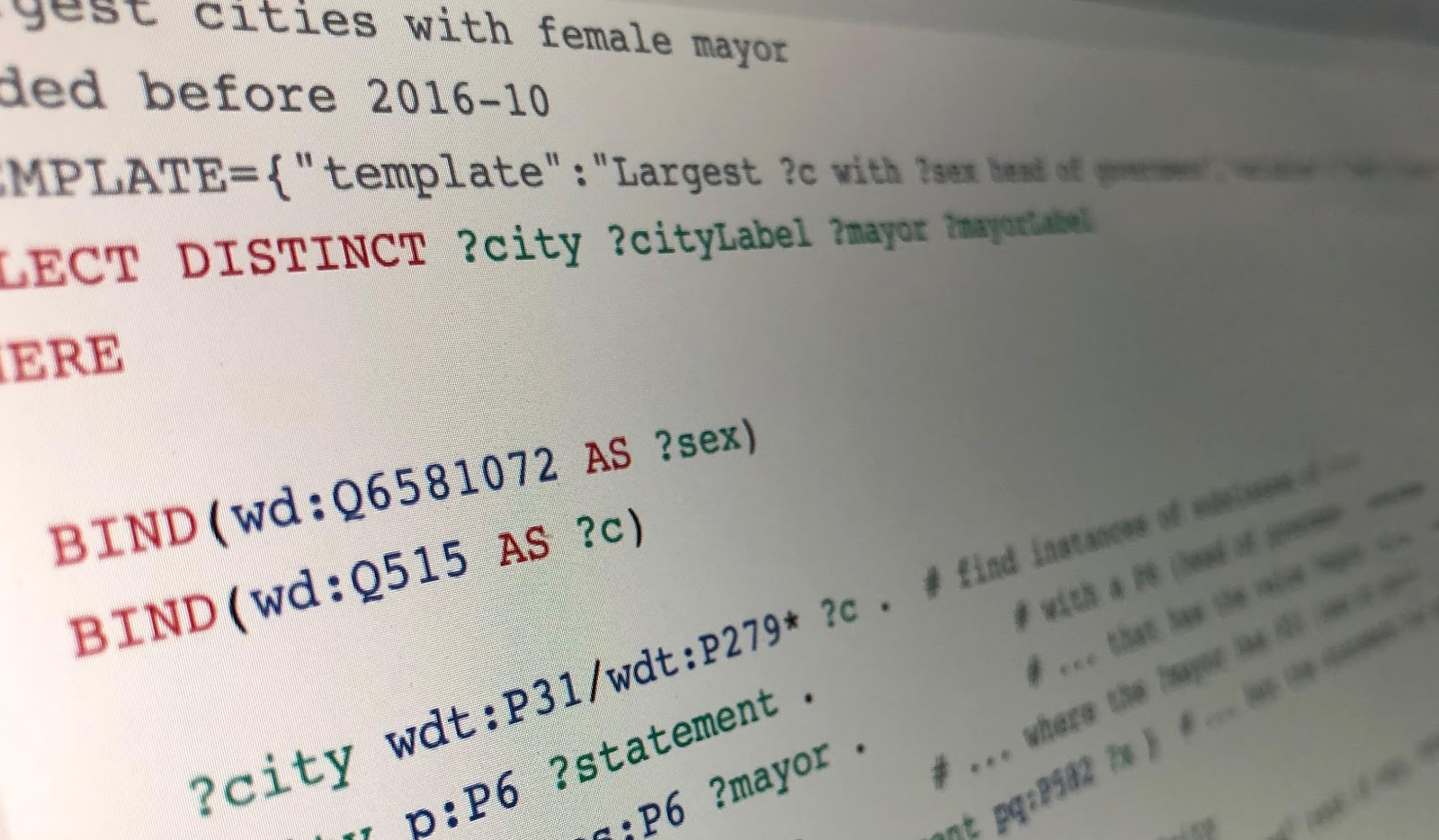

Wikidata Query Service (WDQS) gives us one way to take all that computable information and actually compute with it. WDQS uses a semantic query language called SPARQL, which is superficially similar to the database query language SQL. SPARQL is also compatible with the idea of computational neutrality; it’s a standard language supported by the standards community and used by many graph databases and not tied to a particular programming language or database implementation.

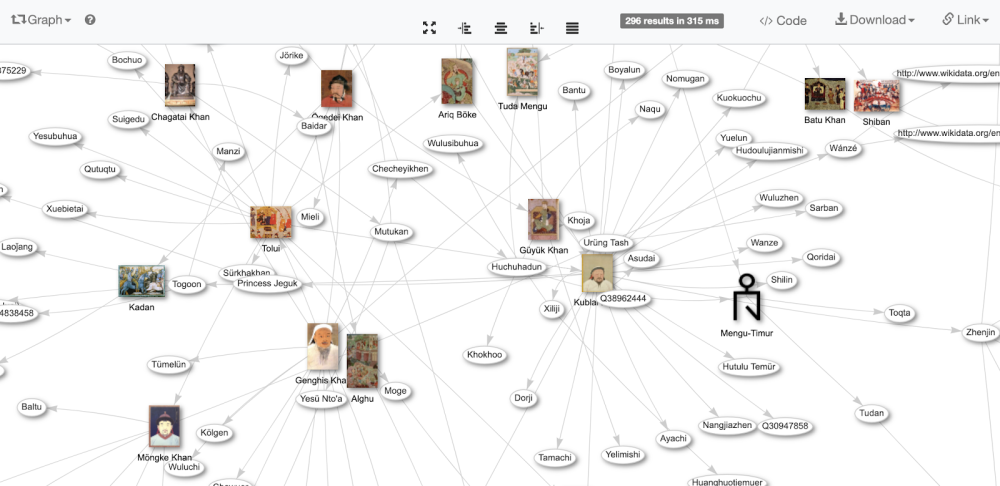

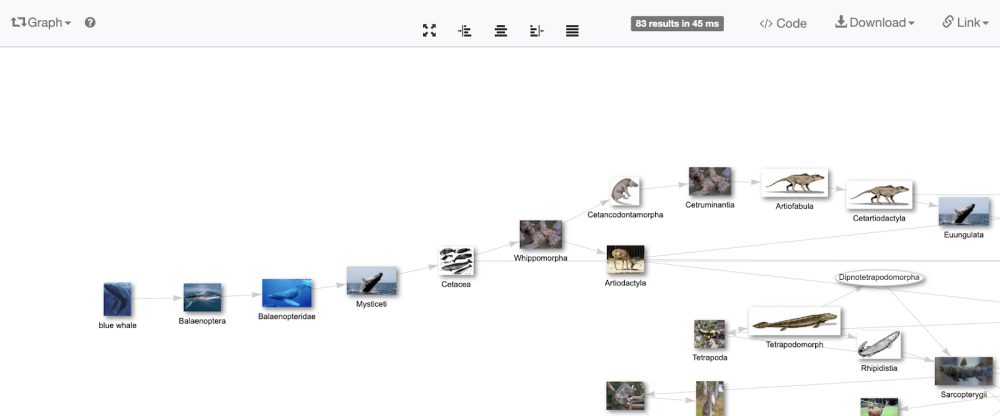

To over-simplify a bit, SPARQL lets you express the information you know and the information you don’t know as a set of partially filled-in triples. The graph database on the backend navigates the knowledge graph created by all the triples to find values that satisfy your SPARQLing requirements.

Sometimes the details of the RDF triples in Wikidata can get a bit arcane because building a really general but useful ontology—a system of representation for things and the relationships between those things—is really, really hard. (It can be so hard, in fact, that a lot of times the best option seems to be to give up creating an ontology from first principles and let users define one on the fly—for example by tagging things however they want to. Such systems have been called folksonomies and include the system of categories on Wikipedia. Wikipedia categories can be very practical, but they also fail to have all of the formal properties of a proper ontology… but I digress.)

Below we have a simplified SQL-ish pseudo-query to find mayors who are women. It’s also Englishified, because in the language-neutral representation of Wikidata, “City” is Q515, “has-gender” is P21, “Female” is Q6581072, etc. Other complexities have also been glossed over, but hopefully, you will still get the idea.

SELECT <city>, <mayor> WHERE

<city> is-a City

<city> has-as-head-of-government <mayor>

<mayor> has-gender Female

<city> has-population <pop>

ORDER BY <pop>

LIMIT 10You can run the real thing at query.wikidata.org. After the page loads, look for the blue “execute query” button at the bottom of the column to the left of the SPARQL text—it looks like a typical “play video” button—and click it. The results come back almost immediately—it’s obviously so much faster than trying to extract the information manually from Wikipedia!

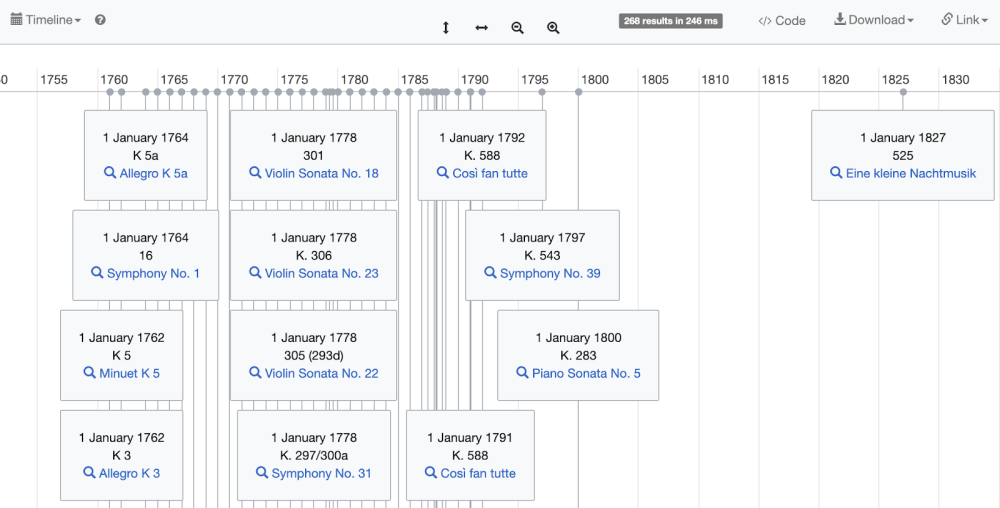

The table of results may not seem too exciting, in terms of format—though it’s been nicely styled for reading in your browser. However, simple columns of data are exactly what many data visualization tools take as input—and several really cool visualization tools have been built into the WDQS interface. Below are some screenshots with links to examples. (Remember to press the blue “play” button for each to run the query and see the results.)

There’s still work to do

Like Wikipedia, Wikidata is edited and maintained by volunteers (and helpful bots!). Given its explosive growth, it’s not too surprising that things sometimes fall through the cracks—also like Wikipedia.

As of this writing, there are a few problems with the information about female mayors in Wikidata. Until early March 2020, Kishori Pednekar was not listed as the Mayor of Mumbai, despite taking office in November 2019. Zandile Gumede, a woman, is still listed as the mayor of eThekwini, despite being replaced by Mxolisi Kaunda, a man, in August of 2019. The Wikidata Query Service also currently presents three female mayors of Caracas—Helen Fernández, Carolina Cestari, and Erika Farías Peña—because their times as mayor do not have beginning and ending data indicated in Wikidata.

Of course, as with Wikipedia, any or all of these problems could be fixed at any moment now by volunteers—like you!

Summa summarum

Of course, this just scratches the surface of everything that you can do with Wikidata and WDQS. Even if you can’t tell SPARQL from a sprocket wheel, there are lots of example queries with interesting visualizations that you can run—just look for “Examples” at the top of the page at query.wikidata.org.

There are many more tools and applications of Wikidata and WDQS out there—including ways to include queries and results from other structured data sources—and new ones are being developed all the time. There’s a lot of good documentation, too. A few places to start include Wikidata Tours and the WDQS docs. There are lots of slides and presentations on WDQS on Commons, including a brief one-page guide to WDQS syntax, a nice intro to Wikidata, and much more. If you (or someone you know) only have a few minutes, there’s a great lightning talk about Wikidata from WMF’s Asaf Bartov on YouTube, too! If you really get into WDQS, you can even get SPARQL help on Wikidata’s “Request a query” page.

And we haven’t even touched on the Wikidata “Lexemes” project, which aims to encode lexicographical information about individual words in the same way that things, concepts, and relationships are already encoded in Wikidata. Like the rest of Wikidata, in the early days, it may seem like a preposterously ambitious goal until it’s an amazing resource you can’t live without.

I think this ridiculous but wonderful quote about Wikidata somehow sums up all that preposterous ambition, how far Wikidata has come, and how far it has to go:

“Until Wikidata can give me a list of all movies shot in the 60s in Spain, in which a black female horse is stolen by a left-handed actor playing a Portuguese orphan, directed by a colorblind German who liked sailing, and written by a dog-owning [woman] from Helsinki, we have more work to do.”

—User:Tobias1984, Wikidata project chat, December 2013

[Thanks to Stas Malyshev for giving me an overview of and historical context for Wikidata, WDQS, and related projects, and for all the work he’s put into WDQS over the years!]

About this post

Featured image credit: Trey Jones

The mayor query in fact goes back to the very first Wikimania in 2005, where we used it in a talk proposing this idea for the first time as a motivating example. Thank you for this awesome write up!