2020: The Year in Vue

By Eric Gardner, Software Engineer, and Anne Tomasevich, Software Engineer, The Wikimedia Foundation

It’s been roughly a year since the Front-End Working Group (FAWG) of the Wikimedia Foundation published a widely-discussed proposal to Adopt a Modern JavaScript Framework for use with MediaWiki. This proposal recommended that Wikimedia technical projects begin using the popular Vue.js framework to build out the next generation of user interfaces across our products.

After much discussion and debate, this proposal was adopted by the Wikimedia Foundation’s Technical Committee (TechCom) in March of 2020, and various teams around the Foundation began experimenting with Vue.

Now that it’s been one year since the initial proposal, it seems like a good time to step back and ask: where do things stand with Vue and MediaWiki today? In what follows we’ll share some of our experiences using Vue within the Structured Data team over the last year.

First steps: SuggestedTags special page

Around the time that TechCom formally approved the RFC to adopt Vue.js for (some) new feature development, the Structured Data team was finalizing a new feature for Commons: computer-aided tagging of images using Google’s Cloud Vision API. Our goal was to make it easier for users to add structured (machine-readable) data to image files by providing computer-generated suggestions which human users could choose to add to a given File page.

The feature lives at a dedicated special page and can be accessed by any logged-in user.

The team had already completed a prototype of the page using OOUI (the Foundation’s traditional in-house UI library), but we decided to spend a few weeks porting everything over to Vue in the Spring of 2020 as an experiment. We were eager to build something with a modern JavaScript framework, given our past experience with Vue and React, and we hoped to determine the efficacy and level of ease of using Vue within MediaWiki.

Experimental approach

This project was an ideal test-bed for experimenting with Vue.js. The feature was designed as an interactive dashboard only available to logged-in users, so we didn’t need to worry about caching or server-rendering pages. We believed that a client-side framework like Vue would be a natural fit for this kind of application.

Our initial hypothesis was quickly confirmed by experience. Within weeks, we were able to recreate and extend the previous prototype, even though we had to re-build some low-level components (equivalent to OOUI widgets) at the same time.

Declarative syntax

One factor that greatly sped up development was the ability to write UI code using a declarative, HTML-like syntax inside of Vue single-file components. This made it very easy to quickly scan code for relevant HTML elements, CSS classes, and the like – as opposed to following a long chain of imperative jQuery or PHP function calls. When some significant design changes were introduced relatively late in development, it was straightforward to rewrite the relevant bits of markup while leaving the rest of the code alone.

Isolated components

Vue encourages developers to break up UIs into small components that are relatively isolated from one another. In OOUI code, it’s common to see components that reach deep into children or grandchildren to manipulate state or call various methods, which can make it difficult to reason about how data flows through the application. In contrast, Vue enforces strict encapsulation: components are expected to pass data down to children and listen for any events they emit, but otherwise, each component should know as little as possible about what goes on inside any other.1

Vuex

Consistent rules about data flow and component isolation will go a long way in making an application easy to comprehend. But for many non-trivial applications, there will inevitably be some global concerns that touch components at a lot of different levels.

In the case of the SuggestedTags interface, most user actions ultimately end up modifying a single data object that represents which suggested tags were approved or rejected for a given image. This data is what gets submitted back to the server when the user clicks the big “publish” button at the bottom of the screen.

This situation ended up being a great use-case for Vuex, the official state-management library for Vue. The ins and outs of how to work with Vuex could fill a whole separate blog post (perhaps we’ll write one soon), but all in all, we found it to be a highly effective and lightweight tool. Using Vuex allowed us to introduce some separation of concerns into our code, creating clear distinctions between the “presentational” state of components (which tab a user is looking at, whether a given button is enabled, etc.) vs. data that is being prepared for eventual submission to our API.

Vuex also allowed us to enforce a degree of type-safety in this critical data, because the state defined by the developer can only be manipulated by special functions called mutations. To ensure that a certain bit of data in the store is always an array, for example (even when empty), the relevant mutations can be written to only use methods like push and shift instead of simply assigning new (arbitrary) values. Having mutations act as “gate-keepers” to the data can guarantee a little bit of type-safety in a language where it is otherwise hard to come by.

Integration with MediaWiki

Finally, this project was a useful test of whether we could easily work with Vue in the context of a typical MediaWiki environment, without relying on any external build tools like Webpack or Babel. The short answer is: yes, we can!

MediaWiki uses a system called ResourceLoader to optimize and deliver front-end assets (CSS, JavaScript, i18n message strings, icons, etc).2 Vue single-file components are structured like HTML, so ResourceLoader’s existing PHP code was able to process these files with minor modifications. Vue templates contain some custom syntax, but the framework includes its own compiler to process this syntax on the fly at runtime (something that’s not really feasible to do with JSX & React). We were still limited to writing ES5 code in our components, however.

This flexibility was a major selling point in Vue’s favor back when the FAWG was evaluating various front-end frameworks. We didn’t want to introduce a bunch of other new technologies like Webpack or Babel for what was essentially an experiment. Vue certainly lived up to its promise here: with a few small tweaks to our legacy delivery system for front-end assets, we were able to get many of the benefits of a modern front-end workflow (single-file components, use of the Vue devtools in ResourceLoader’s debug mode, etc.) Webpack has its uses, but it’s also notoriously complex, so it’s great to have the option not to use it in a simple project.

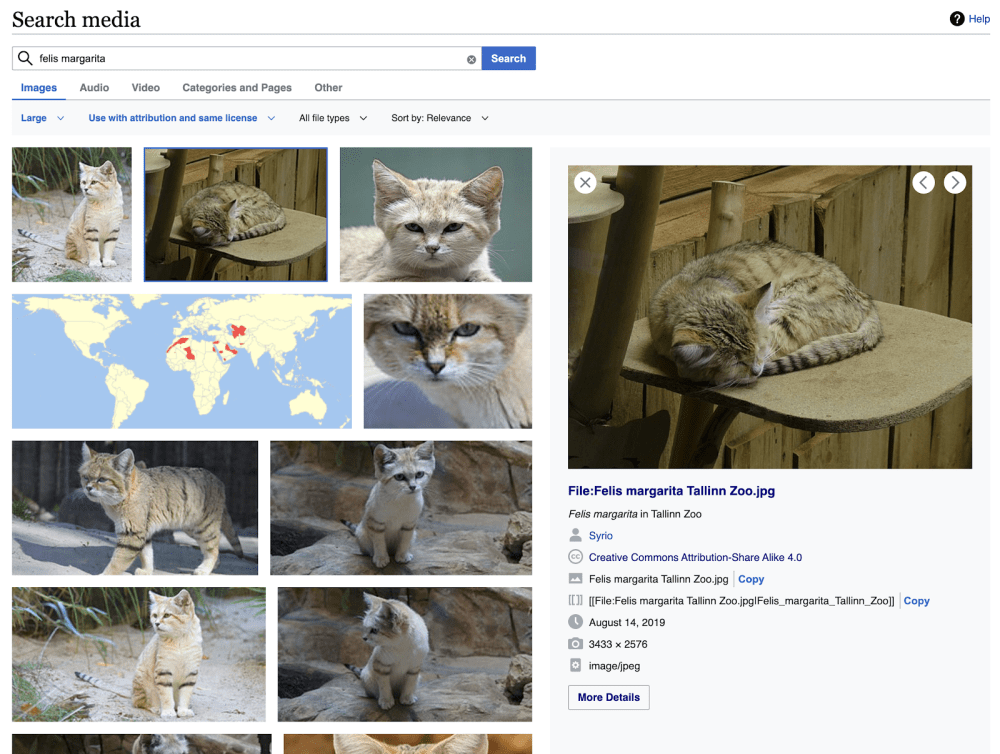

Next steps: Commons MediaSearch

After our overwhelmingly positive experience building the SuggestedTags page with Vue, we were excited to apply what we learned to a new project: the Special:MediaSearch page on Wikimedia Commons. This project would be significantly larger in terms of scope and visibility than the SuggestedTags page, and we predicted that using Vue would allow us to both rapidly build and iterate on features and to manage a more complex state.

This page contains a search input with an autocomplete dropdown, a tab layout with a tab for each media type (images, videos, etc.), search filters, search results, and a preview panel that appears when a user clicks on a result. Additional features, such as “concept chips” that display and link to related search terms, are still being developed.

Additional base components

As part of the SuggestedTags project, we had recreated several OOUI widgets (like buttons and messages), and we were able to reuse and extend these components during the development of MediaSearch. We created a separate directory for the reusable, project-agnostic components that became the building blocks of our custom UI components, and refer to these as base components. Building each base component involved careful evaluation of the associated OOUI widget, since the existing widgets represent years of iterative improvements, particularly in crucial areas like accessibility and usability. We aimed to carry this knowledge over to our new Vue components and to ensure that our components looked and felt like the OOUI ones.

To meet our deadlines, we aimed to create the simplest possible version of each base component that was sufficient for our use cases (plus a little more, when we had the time and inclination). That said, this was a fruitful exercise, and we hope to more thoroughly break down the experience in a future blog post.

Mixins and plugins

As the complexity of the app grew, we called on some additional Vue features to reduce repetition and component complexity: mixins and plugins. In general, we aimed to keep component files as simple to understand and linear as possible, which is one of the benefits of single-file components. However, in a few cases, including everything needed for a component in its file would have meant a lot of repetition and unnecessarily long component files.

Our first case for a mixin was a fairly classic one: we needed a different Vue component for each result type (ImageResult, AudioResult, etc.), but all of the result components shared a significant amount of props, computed properties, and methods. Instead of repeating this code in each of the result components, we created a mixin containing the shared code that each result component could include, giving it access to those properties and methods.

We also found mixins useful for a special case: the parent component of the autocomplete input needed to make an API call to fetch autocomplete results, then do a lot of processing of the results before sending them down to the input for display. Rather than cluttering the parent component with a lot of autocomplete-specific logic, we sequestered this code into a mixin in the interest of separating different concerns.

While mixins contain reusable code for specific components, plugins add reusable code to all components in an application. The $i18n plugin exists in MediaWiki core and provides all components with access to MediaWiki’s internationalization system, which was critical to building a translatable interface in Vue. We built an additional small plugin that submits events to MediaWiki’s modern event platform, which reduced the amount of code needed each time we logged something.

A server-rendered fallback

In order to serve users with older browsers or with JavaScript disabled, we needed to build a server-rendered UI that could provide the core functionality of the page. We knew that all users needed to be able to perform a search and see results, to load more results after they review a batch, to go to the file page of a result they wanted to inspect further, and to access all media types. We viewed additional functionality—autocomplete suggestions, loading results without reloading the page, the details panel, and loading more results on scroll—as progressive enhancements available to users with JavaScript.

Unfortunately, this meant some code duplication: the logic to build and send off a search API request then process the results exists in both PHP and JavaScript, and a significant amount of the JavaScript UI is duplicated in a mustache template used on the server-side.3 1In the future, we hope to work out a way to support server-side rendering of Vue components in MediaWiki so that we don’t have to duplicate UI code in two different languages. Watch this space!

A bright future for MediaWiki front-end development

After nearly a year of using Vue.js to build features within MediaWiki, we couldn’t be more excited to continue this journey and to see more MediaWiki developers take advantage of the benefits Vue.js has to offer. We hope this inspires you to try Vue.js and we would love to hear about what you’re building with Vue in 2021!

Footnotes

- There are some “escape hatches” for edge cases (like using $refs or $parent to reach into a different level of the component hierarchy), but developers are encouraged to avoid using them unless absolutely necessary. ↩

- ResourceLoader provides limited support for module bundling and no ability to “transpile” JS code into the older format required for compatibility with legacy browsers like Internet Explorer. This is a departure from the current mainstream approach to front-end web development, which relies on an increasingly complex chain of tools like Webpack, Babel, and NPM to automatically process modern code into a backwards-compatible format. ↩

- We were able to share styles between the two versions of the UI, but that meant pulling the styles out of Vue single-file components into separate LESS files that ResourceLoader can add to the page before JavaScript loads, meaning we have two files per component. ↩

About this post

Featured image credit: 20180126 FIS NC WC Seefeld 850 1484, Granada, CC BY-SA 4.0

thanks a lot.

hello is a good article.. very informative

thanks you

hello is a good article.. very informative

thanks you

Huge Vue fan of both Vue and Wikimeda. I’m glad Vue worked for your use case.