The journey to Thumbor, part 2: thumbnailing architecture

By Gilles Dubuc, Senior Software Engineer, Wikimedia Performance Team

Thumbor has now been serving all public thumbnail traffic for Wikimedia production since late June 2017.

The stack

Like everything we serve to readers, thumbnails are heavily cached. Unlike wiki pages, there is no distinction in caching of thumbnails between readers and editors, in fact. Our edge is Nginx providing SSL termination, behind which we find Varnish clusters (both frontends and backend), which talk to OpenStack Swift – responsible for storing media originals as well as thumbnails – and finally Swift talks to Thumbor (previously MediaWiki).

The request lifecycle

Nginx concerns itself with SSL and HTTP/2, because Varnish as a project decided to draw a line about Varnish’s concerns and exclude HTTP/2 support from it.

Varnish concerns itself with having a very high cache hit rate for existing thumbnails. When a thumbnail isn’t found in Varnish, either it has never been requested before, or it fell out of cache for not being requested frequently enough.

Swift concerns itself with long-term storage. We have a historical policy – which is in the process of being reassessed – of storing all thumbnails long-term. Which means that when a thumbnail isn’t in Varnish, there’s a high likelihood that it’s found in Swift. Which is why Swift is first in line behind Varnish. When it receives a request for a missing thumbnail from Varnish, the Swift proxy first checks if Swift has a copy of that thumbnail. If not, it forwards that request to Thumbor.

Thumbor concerns itself with generating thumbnails from original media. When it receives a request from Swift, it requests the corresponding original media from Swift, generates the required thumbnail from that original and returns it. This response is sent back up the call chain, all the way to the client, through Swift and Varnish. After that response is sent, Thumbor saves that thumbnail in Swift. Varnish, as it sees the response go through, keeps a copy as well.

What’s out of scope

Noticeably absent from the above is uploading, extracting metadata from the original media, etc. All of which are still MediaWiki concerns at upload time. Thumbor doesn’t try to handle all things media, it is solely a thumbnailing engine. The concern of uploading, parsing and storing the original media is separate. In fact, Thumbor goes as far as trying to fetch as little data about the original from Swift as possible, seeking data transfer efficiency. For example, we have a custom loader for videos that leverages FFmpeg’s support for range requests, only fetching the frames it needs over the network, rather than the whole video.

What we needed to add

We wanted a thumbnailing service that was “dumb”, i.e. didn’t concern itself with more than thumbnailing. Thumbor definitely provided that, but was too simple for our existing needs, lacking support for numerous document, video, and other multimedia formats hosted by Wikimedia Commons, our open media repository. We wrote plugins to add the following features:

- Thumbnails of PDFs, DjVu documents, and STL 3D models.

- Thumbnails of videos (WEBM and OGV).

- ImageMagick engine, for faster processing.

- VIPS engine, to reduce memory footprint when handling large files (>1GB).

- The ability to run multiple format engines at once.

- Support for multipage-aware thumbnails (e.g. page 3 of a PDF).

- Handling the Wikimedia thumbnail URL format.

- Loading originals from Swift.

- Saving thumbnails to Swift.

- Open videos efficiently with range requests.

- Various forms of rate limiting and throttling.

- Live production debugging with python-manhole.

- Sending logs to Logstash (ELK stack).

- Wikimedia-specific filters, such as conditional sharpening of JPGs to match MediaWiki ecosystem expectations and community conventions.

We also changed the example files included in the Thumbor project to respect open media licenses, and wrote Debian packages for all of Thumbor’s dependencies and Thumbor itself.

Conclusion

While Thumbor was a good match on the separation of concerns we were looking for, it still required writing many plugins and a lot of extra work to make it a drop-in replacement for MediaWiki’s media thumbnailing code. The main reason being that Wikimedia sites support types of media files that the web at large cares less about, like giant TIFFs and PDFs.

In Part 3: Development and deployment strategy, I’ll describe the development strategy that led to the successful deployment of Thumbor in production.

About this post

This post was originally published on our Phame blog.

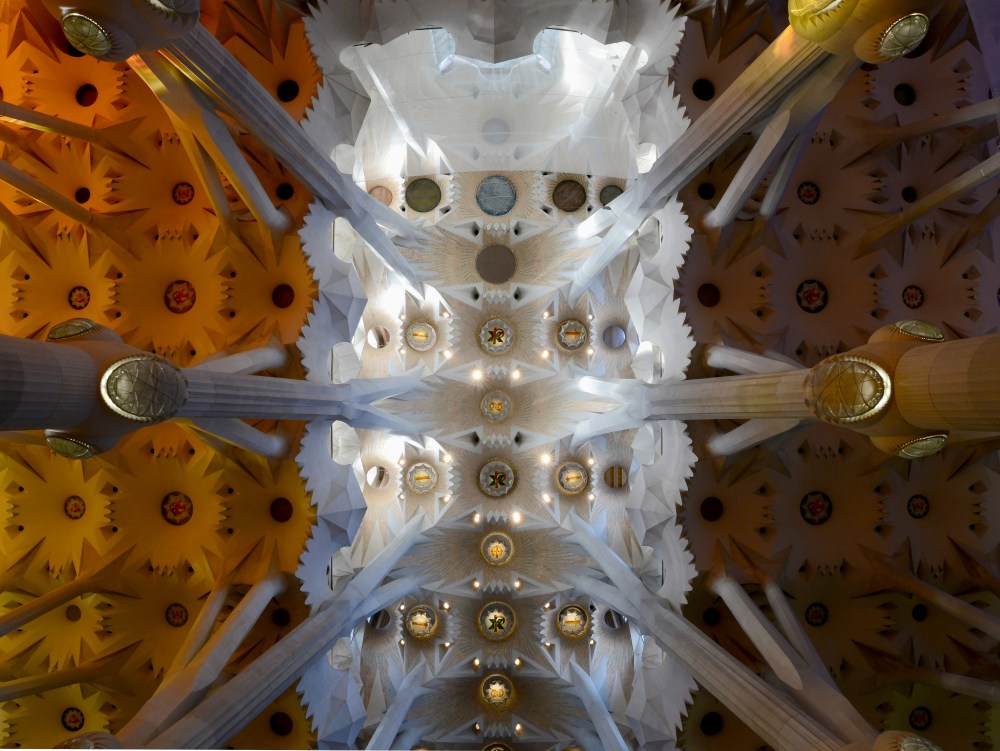

Featured image credit: Sagrada Familia by Alvesgaspar (CC BY-SA 4.0).