Permuting Khmer: restructuring Khmer syllables for search

By Trey Jones, Senior Software Engineer, Search Platform, The Wikimedia Foundation

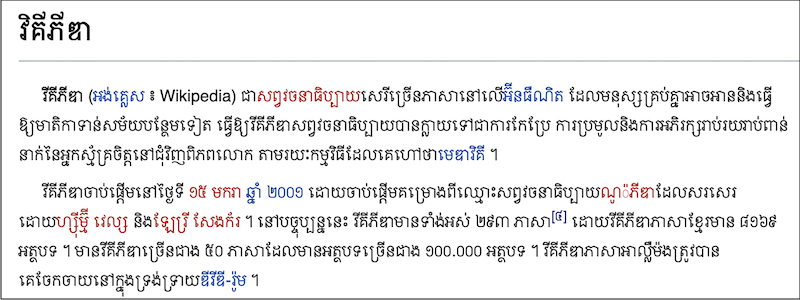

Khmer, also called Cambodian, is the official language of Cambodia. The Khmer script is a syllabary closely related to the scripts for Thai and Lao, and more distantly to all the Brahmic scripts. Khmer is written left-to-right in syllable groups, without spaces between words—though that’s not its most complicated feature!

Syllables govern the world

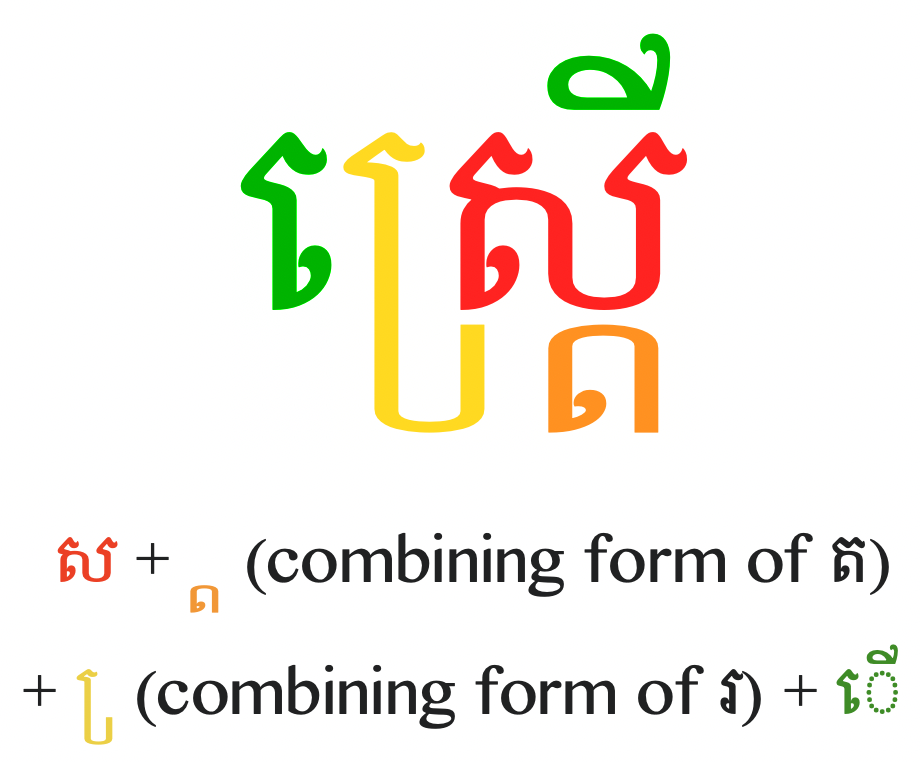

Khmer text is composed of syllables, which are built around a base character that represents a consonant and an inherent vowel. Up to two additional supplementary consonants may be added to the syllable by stacking them underneath the base character (usually). The inherent vowel of the base character can also be changed by adding a different vowel sign to the syllable. Other diacritics may also be added to alter the pronunciation of the consonant or vowel.

The various elements that glom on to the base character can attach themselves below, above, to the left, or to the right of the base character, and sometimes multiple elements can stack, especially above or below the base character. Some supplementary consonants can also go to the side of the base character rather than below, and some of the vowel signs have two parts—one to the left, and the other above or to the right. Some diacritics change shape or location in the presence of other diacritics—for example, if both would normally go on top of the base character—presumably to keep things from getting too crowded.

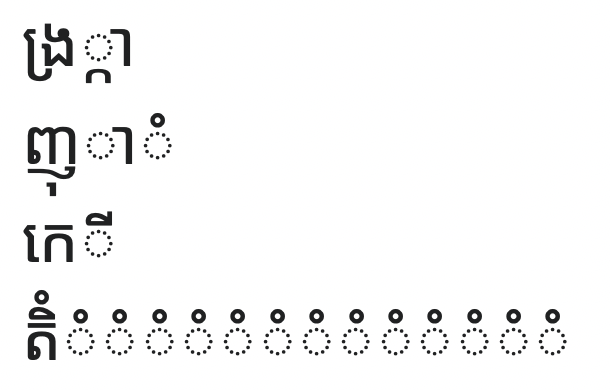

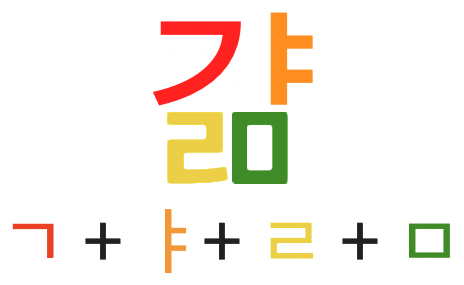

In the example below, the base character, “sa”, is in red. The first supplementary consonant, “ta” (in orange), goes below the base character. The second supplementary consonant, “ro” (in yellow), goes mostly to the left, though a bit of it is below the base character. The vowel sign, “oe” (in green), is in two parts—one goes to the left of everything else, and the other goes above the base character. The transliteration of this syllable is “straeu”. The final vowel, which determines the vowel for the whole syllable, is named “oe” in Unicode, though it is phonetically transcribed as /aə/, and it can be transliterated into Latin script as “aeu”—just to keep things confusing for non-speakers!

Order is the law of all intelligible existence

Unicode support for Khmer is very different from, for example, Hangul—the script for the Korean language. Modern Hangul has 40 basic letters that can be combined into the 11,172 syllables in common usage, all of which are available as individual Unicode characters. For example, 걂 (HANGUL SYLLABLE GYALM) is a single pre-composed character, even though it is made up of four component characters: ᄀ + ᅣ + ᄅ + ᄆ. [1]

In Khmer, the task of composing characters into syllables is left entirely to some combination of the font, the operating system, and the application being used. [2] Back in the digital stone age—the 1990’s and before—support for Khmer was spotty and inconsistent, like the support for many non-Latin (and even non-English) writing systems. [3] As a result, different fonts and different operating systems support typing the code points of a Khmer syllable in different orders, in that they will render the resulting syllable the same (or very nearly the same). This happens because—to simplify a bit—there isn’t really an obvious linear order to the elements that glom on top, to the left, and below the base character, so any semi-reasonable order will do.

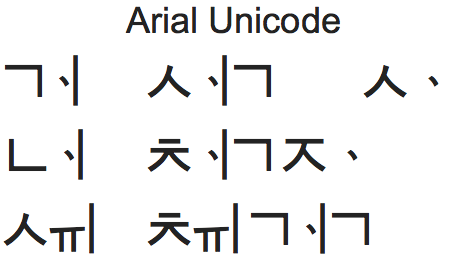

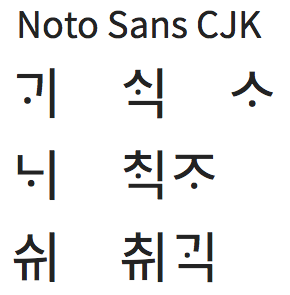

The Unicode Standard sets out a canonical order for Khmer syllable elements, which corresponds to the order the elements are spoken—though there seem to still be a few elements that are ordered arbitrarily.[4] Incorrect ordering should result in glyphs with a dotted circle (◌), showing that they aren’t combining correctly, but many fonts and applications will still render non-canonical orders perfectly fine, or at least reasonably well, and some don’t show the dotted circle even when they render poorly.

Another issue is that for some Khmer diacritics, multiple copies can render directly on top of each other so that you can’t easily see that there are multiple copies. This can apply to vowels, supplementary consonants, and other diacritics.

A similar but much smaller scale problem in English is that é can be either a single character or two characters (e + ´) composed together—but in Khmer this is turned up to 11! A more analogous example would be if the character sequences scrum, srcum, sucrm, and scruuuuum all looked identical.

All of this variability causes great difficulty in search because two words that look exactly the same could underlyingly be composed of very different sequences of characters.

Example is always more efficacious than precept

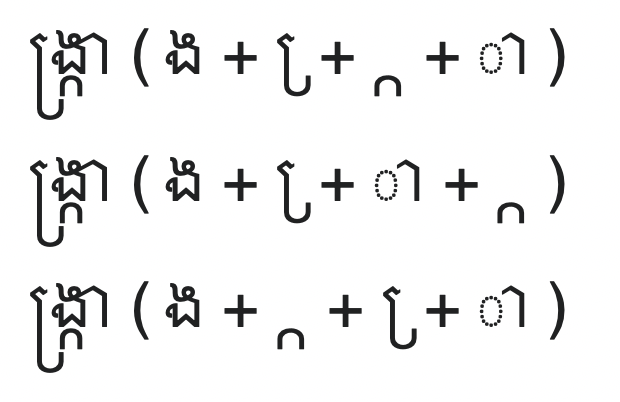

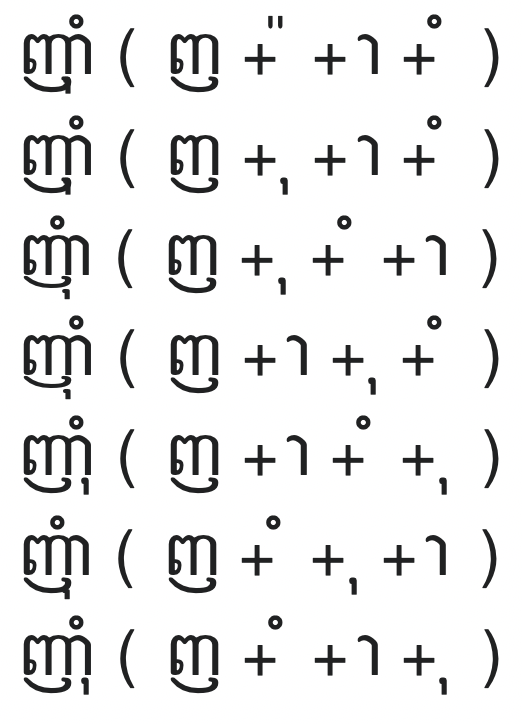

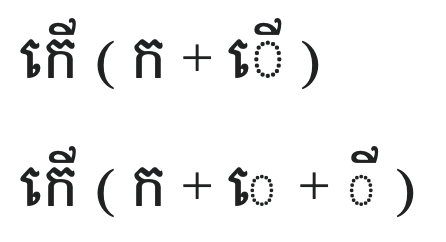

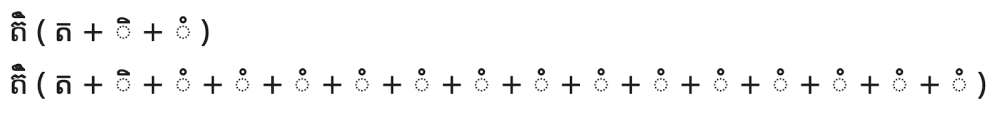

Below are some screenshots of examples of Khmer syllables that look the same or very similar, despite the different orders of the syllable elements. I’m providing screenshots because the exact behavior of any given non-canonical sequence of characters may differ depending on the font used, and I don’t know what fonts you have available, Dear Reader.

All of these are examples I found on the Khmer Wikipedia.

In this group, the supplementary consonant (the third element in the first row, which looks like an intersection symbol: ∩), can appear between or after any of the other elements. This is analogous to the scrum, srcum, sucrm case above.

In the next set of examples, the rendered syllables are not exactly the same, but are probably close enough to go unnoticed if you are reading quickly. Not only can the final three elements appear in any order, in the first example, the second element is a completely different character—it looks like a double quote (“) rather than a comma (,). It is moved down and below the base character because of the presence of the last element (which looks a degree symbol: °)—there isn’t room for both above the base character.

As mentioned before, some vowel signs are made up of two parts. In this case, those two parts each exist as independent characters. If used together, they can look exactly like the single vowel sign. This is a bit like using “vv” instead of “w” in English.

This example shows the most duplication I found of any diacritic. The two characters above the base character don’t render particularly well anyway, so the slight increase in thickness of the circle is almost impossible to notice at reading speed. This is analogous to the scruuuuum case above—though it is more like scruuuuuuuuuuuuuum!

Finally, these are examples of how some of the malformed syllables above should appear, according to the Unicode specs—but, of course, depending on your fonts, OS, and apps, your mileage may vary.

Just figure out what’s next

Obviously, having this kind of invisible variability can make some sequences of characters almost impossible to find using normal text-based search, which makes the search on Khmer-language wikis less effective.

So, how big is the malformed Khmer syllable problem, and what can be done about it?

After much research and experimentation, in the fall of 2019 I built a prototype tool that reads in Khmer text, identifies syllables, and reorders the malformed ones. I’ve been able to use feedback from Khmer readers to improve it, and to get a sense of the kinds of problems that exist on Khmer-language wikis. The tool also made it easier to see how frequent the problem is.

The good news is that syllable errors on Khmer Wikipedia are fairly rare—only about 0.17% of syllables in my sample of articles needed to be reordered. Also, the reordering algorithm works very well—only 0.39% of the 0.17% of the reorderings (or, 0.00067% of the total) were erroneous, and most of those were the result of obvious typos in the original text. Errors are noticeably more common in queries on Khmer Wikipedia—1.3%—but the error rate in fixing them is about the same (0.38% of the 1.3%, or 0.0049% of the total).

The plan is to use the prototype as a basis for building a plugin for Elasticsearch—the search engine that underlies on-wiki search—and deploy it to Khmer-language wikis. When syllables are reordered, both the original and reordered syllables will be searchable.

You can track progress on the task on Phabricator. You can read more details about my investigation into Khmer syllable reordering on Mediawiki, including a bunch of example reordered syllables and discussion about them; you can also find details of the syllable reordering algorithm, and all the best references I found while learning about Khmer syllables, if you want to read more!

__________________

[1] Here is the color-coded breakdown of 걂 (HANGUL SYLLABLE GYALM) into ᄀ + ᅣ + ᄅ + ᄆ (g + ya + l + m).

[2] For rare, historical letters in Hangul, it is up to the font, OS, or application to combine them into syllable blocks, because no pre-composed Unicode characters exist. Some fonts are better than other fonts—just as with all Khmer syllables:

[3] The online Cambodian Information Center’s “Khmer Fonts” page (cambodia.org/fonts/), where I downloaded many Khmer fonts, offers this bit of unofficial history:

As computer and internet industry gain influence and market in Cambodia, several types of Khmer fonts have been developed… Most of them were not developed by using Unicode or meet the guideline of the Unicode Standards. However, all of these fonts have been widely utilized with word processing, such as Word in Microsoft Office. Because many of these fonts were neither developed using Unicode Standards nor adopted by makers of World Wide Web (WWW) browsers, many Khmer fonts were not readable without special library drivers.

[4] There is a lot of material and discussion from the Unicode Consortium about Khmer syllables. Chapter 16.4 of Version 13.0 of the Core Specification [PDF] includes a section on Ordering of Syllable Components (p 662 of the standard; 27th page of the linked PDF), if you are either super interested in the nerdy details—like me—or you need help falling asleep at 3am.

About this post

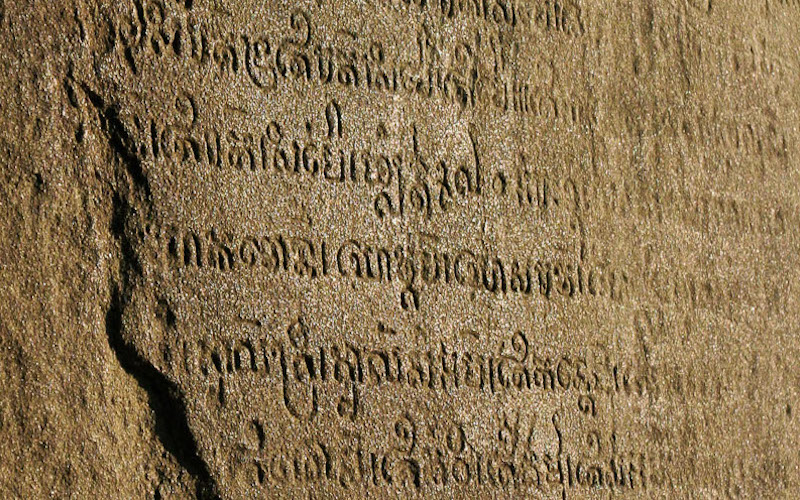

About Featured Image: Khmer inscription from Prasat Kravan (ប្រាសាទក្រវាន់), a 10th-century temple in Angkor, Cambodia. (Image cropped from “Prasat Kraven – Doorway Inscriptions”, by Greg Willis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Section headings are quoted from John Selden, John Stuart Blackie, Samuel Johnson, and Steve Jobs.